How to prioritise wellbeing while working therapeutically in lockdown

Comments Off on How to prioritise wellbeing while working therapeutically in lockdownLast month, we returned to our regular blogging schedule with an article addressing the assorted challenges many have encountered during the ongoing quarantine procedures – particularly those affecting us in the field of counselling and psychotherapy. In the article, we invited you to share your own experiences in this area, including any new obstacles that you have faced in the course of providing your services, any new skills obtained, and any unexpected benefits that you’ve identified. Thank you so much for your feedback – it has been enlightening, useful and encouraging to see the many different ways we have all been able to rise to meet the challenges of the past year. Thank you, too, for the clear care and dedication everyone has obviously been showing to vulnerable clients and charges, during what has undoubtedly been one of the most complex and difficult times in the lives of many who were already struggling.

In this article, we will be looking at some of the most helpful lessons that you have shared with us over the last few weeks. It’s our hope that you will find this collation as useful and interesting as we have, and that you will be able to use these ideas to improve not only the wellbeing of your clients, but also the wellbeing of you, the practitioner, in these largely-continuing circumstances of remote working, learning, caring and living, both in and out of work.

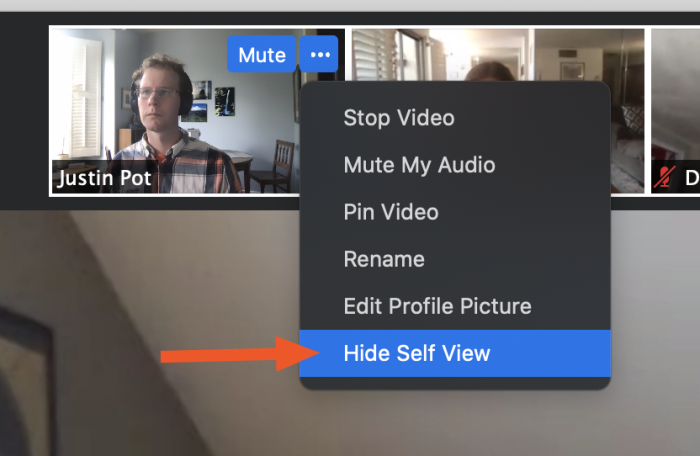

First and foremost, one of the most popular and sensible suggestions we have encountered is to deactivate the self-view window during meetings and sessions conducted over video chat. This advice comes after the publication of a research paper in the journal Technology, Mind and Behaviour which explores how sustained viewing of your own face in real time will cause us to become overly vigilant of our appearance.

Speaking on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, the study’s author Jeremy Bailenson elaborated that “decades of psychology research shows that when you’re looking at yourself we scrutinise ourselves, we evaluate ourselves, and this over time causes stress and negative emotions. When we’re forced to look at ourselves in a real-time video or mirror, we do behave as an idealised version of ourselves. In other words, we try to be the best person we can be, but that comes at a cost.”

In addition to the universal benefits of avoiding this unnecessary stressor, the impact of this wisdom is much more significant within a therapeutic context. Attending counselling or therapy is inherently an exercise in vulnerability and self-awareness; this is true whether you are receiving clinical supervision from a professional peer, or engaging in mandatory assessment within sensitive circumstances (such as you might in cases involving the family justice system, for example). Much of the ongoing work required of the clinician in these and other contexts involves establishing rapport, grounding dysregulation and otherwise working to establish a sense of ease and comfort within the therapeutic environment. Though there is a great deal of extant literature on how to achieve this within a traditional therapy room, it’s clear that attempting this remotely requires its own unique approach. Mitigating this additional source of anxiety and scrutiny could be helpful in overcoming some of these additional obstacles of online vulnerability, both for client and practitioner.

Zoom is perhaps the most popular application used for this purpose, and contains a very simple in-built method of hiding self-view. Full tutorial accessed at https://zapier.com/blog/hide-myself-in-zoom-meetings/

Another potential benefit of removing the self-view function is to prevent additional distractions. As many of you will likely be aware at this point, it’s extremely difficult to consistently avoid the occasional glance at a miniature recording of your own face, especially sustained over the course of the day. This periodic flitting of the eyes around your screen can be especially unnerving to a client who is likely to experience anxiety of whether they have your full attention during a sensitive discussion, to give one example. Removing this distraction can help practitioners and client alike focus more on the person in front of them, and help to encourage more of a natural approach to conversation – how often do we talk in-person while watching our own faces?!

In a similar vein to the above, it’s wise to close any additional applications that are open or running in the background while speaking remotely through your computer or phone. Unexpected notifications during a session or meeting can be an impolite distraction in this way, even if they are muted, and can disrupt your focus while attempting to remain present and congruent with the client. Clients who are sensitive to the attention of others may not see or hear the notification you have received, but they may well note the lapse in your focus.

The benefit of muting other notifications for an uninterrupted digital session may be experienced from both ends of the call. If it is appropriate, you may find it beneficial to introduce this boundary as an entry in the contract that you draw with your client during initial sessions, or when transferring an existing clinical or professional relationship to a new platform. Whether formal or informal, this agreement can explicitly set a standard for the priorities of your attention in a way that is mutually reciprocal and respectful. There may well be cases where this is not practical or helpful for the client; there needn’t be a hard and fast rule if this makes them uncomfortable, or if they are conscious of needing to be contactable (eg. someone is dependent on them). Your discretion is key here.

More broadly, it may be worthwhile to establish a shared understanding of acceptable conduct with your client. If this is not something you already do, it may well be worth setting aside a few minutes at the start of the session to discuss what you both find to be conducive to a private, attentive interaction – this may include factors such as what rooms in the house to take the call in; whether it’s sensible to have a drink of water to hand, but not any other snacks; whether the client is comfortable with physical notes being taken, etc. These are questions that often needn’t factor in, or are otherwise taken as a given in traditional, in-person settings; yet, they may be unhelpful to presume as a foundation when engaging online.

Speaking of physical notes, if you usually generate anything written or material (eg. notes, recordings) during a session that you would share with your client in a face-to-face setting, you or your client may find it beneficial if this is maintained. Sending everything to the client that they would normally see may be a way of preserving some of the more easily-transferable elements of meeting, whether this is done electronically or via post.

With this in mind, it’s worth mentioning that agreeing the parameters of contact can also be a sensible opportunity to set some contextualising groundwork. Making use of more modern delivery platforms makes it more likely than ever that clients will receive access to your working email address or phone number. Being firm about the boundaries of this contact is therefore essential. It may help to transition into this discussion by first confirming explicitly how and when you plan to initiate the call, or at what time you will be sending them a zoom link, etc.

In terms of expressing yourself clearly to avoid your intent becoming lost in translation, it has been imparted to us that many clients are likely to respond well to an occasional verbalisation of affect or internal process. It may seem trite or cumbersome at first to make a point of announcing that you are considering what a client has just said, or pointedly describing the emotions that your conversation elicits, but it is important to remember how awkward and uncomfortable the experience of navigating silence and gauging body language across a screen can otherwise be for some people. Perhaps use your better judgement to determine where these techniques may individually prove a benefit or a hindrance.

Lastly, consider how receiving therapy within their living space, rather than an external location, may increase the need for some clients to receive additional support in returning to baseline comfort and mood after a particularly burdensome session. Making time to ensure that appropriate grounding or mindfulness work can be conducted at the close of a session could make a significant difference to how safe and content a client may be able to feel in their home afterwards.

Does the article correlate with your own experiences? Are these tips helpful? Are there any other topics that you would like to hear us cover in future? Please let us know by sending an email to us at office@jsapsychotherapy.com

A full list of the professionals working as part of this practice on a full time or associate basis can be found here.

Lastly, if you are a counsellor or psychotherapist who is looking for freelance work at the moment, please consider joining our team of associates.