Trauma-informed therapeutic caregiving – What makes a therapeutic model?

Leave a CommentIn recent years, there has been an ever-increasing trend towards recognising and acting on the importance of residential care for children and young people in the care system to be conducted in a way that is fundamentally therapeutic in nature. More providers than ever are adopting such an approach in an attempt to provide therapeutic care rather than mere accommodation, or worse, containment.

However, from conversations that we have had with various providers in the industry, it seems that the criteria of what constitutes therapeutic care is not as widely agreed upon as its overall necessity. Many providers who are making earnest changes to their provisions to achieve this are finding that regulatory bodies such as Ofsted are asserting that further or alternate changes must be made before these outcomes can be considered met.

Further, it seems that much of this confusion is occurring as a result of the understanding that the most direct means of meeting these stringent goals is to approach external clinicians to source therapeutic intervention for the children and young people in question. However, providing therapy on its own isn’t all that’s required for a child’s placement to be considered as therapeutic care.

True therapeutic care, wherein a child or young person is supported to recover from the trauma that they have endured, can only be achieved within a cohesive framework of trauma-informed working that is integrated throughout the entire provision, not merely as an additional modular element to be contracted on top of it.

In this article, we will be setting out what we understand to be the four key defining elements of a therapeutic model. It’s our hope that by outlining the essential features that make a therapeutic model recognisable and functional as a therapeutic model, we can make the process of devising one much more approachable for providers who are keen to integrate therapeutic care into their practice but are currently being stalled by how vague and abstract the process of achieving this can be.

To help illustrate and contextualise these elements, we will also be providing examples of the therapeutic model that we’ve helped to formulate for use in our sister company Life Change Care, known as the TIER system.

What is a therapeutic model?

Simply put, a therapeutic model is the overall framework of trauma-informed care that your provision will use as a reference point to inform the operation of the homes and the care of the children and young people. Much like each child in care will have an individual care plan that is worked from to recognise their individual needs and tailor their support, building upon this with a trauma-informed approach on both a macro and micro scale will transform the caring process into one that is designed with a therapeutic perspective that can be followed to achieve therapeutic care.

This is relevant when considering the aforementioned half measure of outsourcing therapeutic care to an external clinical provider. A child or young person can receive a course of therapy and receive therapeutic care from their assigned clinician for an hour a month/week on an individual basis, but if this doesn’t form a component of an overall therapeutic model that the provider is working from, then it will only exist in isolation and the child will be returning to a home environment which is not therapeutic.

As such, therapeutic care becomes something that they leave the provision to receive for significant minority of their time, rather than something with is actually integrated into their lived environment. This is what assessors are looking for providers to be able to demonstrate.

In fact, many of the intended outcomes of therapeutic intervention, especially where trauma recovery are concerned, can’t be expected from taking on a case where the child’s home environment is not conducive to this. It has been the case where we have been unable to agree to supply these services for provisions who have inquired about them in the past, on the grounds that they don’t have a therapeutic model in place that our therapy could fit into.

Element 1 – Trauma assessment

The first element to be decided on of any therapeutic model also constitutes the first stage of the process of putting it into place for any new child or young person entering your care. In order for your care to be considered trauma informed, you first need to be informed of the specific impact of developmental trauma for any given individual child. Since the effects of trauma are different for everyone, so too will they have unique needs, difficulties and behaviours to recognise and accommodate when attempting to provide care for them.

As such, there needs to be a standard assessment tool in place that is always employed at the beginning of the care process, beyond the background context that has been included in a referral document or anecdotal observation (though these can both be helpful in and of themselves). This is to establish a reliable insight into the complexities of the specific developmental trauma that each and every child has experienced, as well as what that means for your care team.

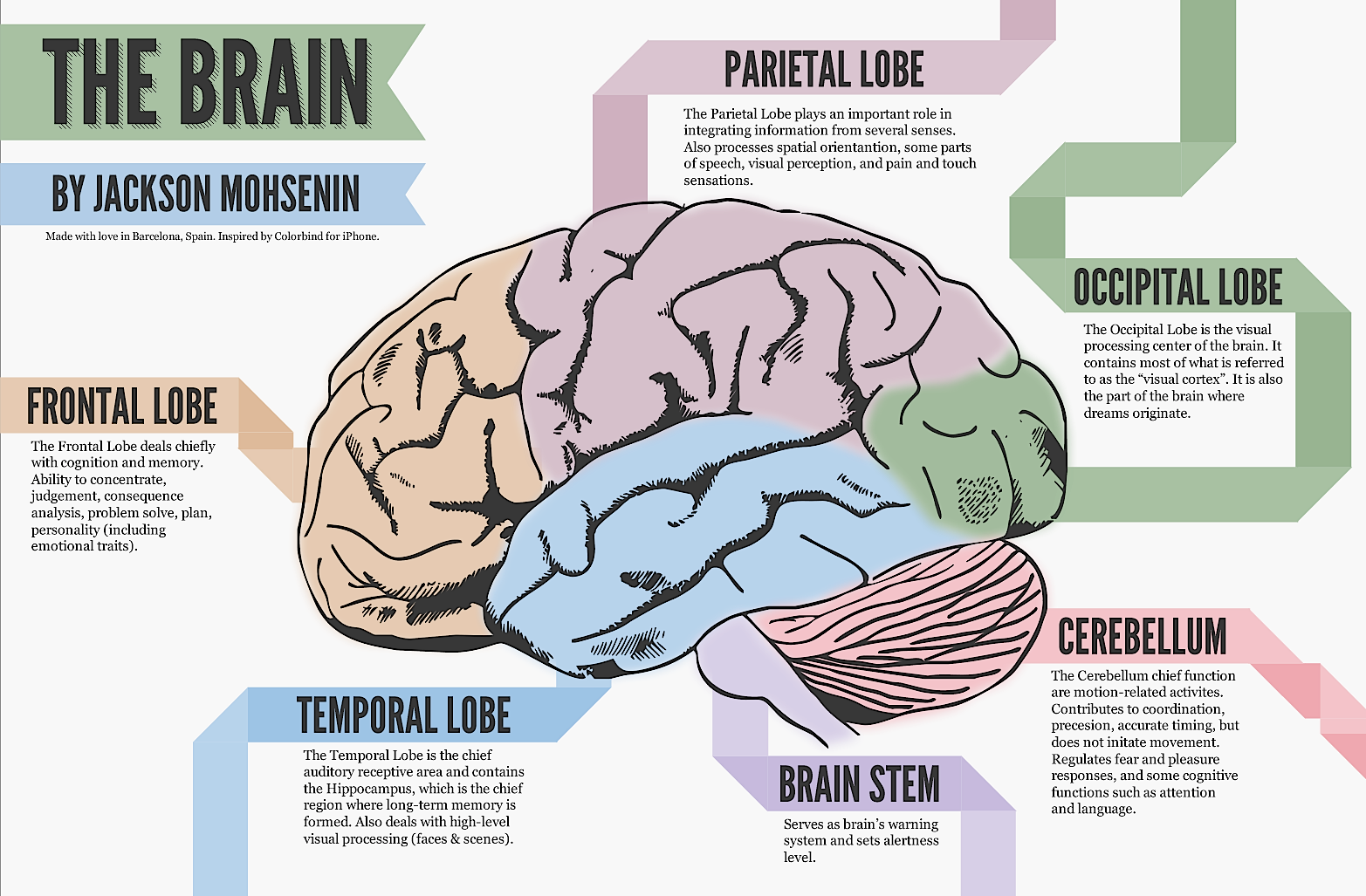

There are various metrics and assessment tools that can be used to ascertain this. For example, the TIER system uses the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics as its trauma assessment tool. NMT assessments examine historical adverse childhood experiences and currently presenting needs and difficulties to identify where an individual has experienced delay in meeting expected age-appropriate milestones in cognitive function, emotional regulation, relational skills and many other areas.

All of these findings are plotted on a ‘brain map’, which can provide a clear indication of where a child will struggle far more than may be expected for their chronological age. This then allows carers to set their expectations accordingly and adjust the child’s care plan to facilitate reaching these key areas of development while therapy is taking place to address the trauma that caused the delay.

Element 2 – Individual response

This brings us to the second element, which is putting the information acquired from the assessments into practice. Once the initial assessment has happened and a child’s care can be considered trauma-informed, there needs to be an established approach for making this information actionable by everyone involved in the process. In short, there needs to be a standardised operating procedure to devise responses for meeting individual presenting needs.

What this looks like will depend on the resources, aims and approach of any given provision, but within the TIER system, the list of potential strategies and interventions that house managers are equipped to pull from in devising an individual response includes the following:

- A child’s individual care plan, to be followed by all staff and made available to relevant professionals. This can include individual goals and expectations for trauma recovery, key working sessions, education & psychotherapy engagement.

- Trauma-informed risk assessments for accommodating the child’s unique needs and vulnerabilities, especially where they might not fall under common sense for the majority of children. For example, inclusion of personal trauma triggers which are likely to make them immediately unsafe.

- Boundaries and key working to place parameters on the child’s own expectations within care and to cooperatively reflect on their own agency and involvement in the recovery process.

- Enrichment activities and daily therapeutic caregiving, both as a means of providing enrichment for unmet developmental milestones and accessible, non-judgemental soothing care for unmet emotional regulation needs.

- The sourcing of tailored education and psychotherapy provision, which can both in and of themselves be informed by an NMT/NME or similar assessment to be the most suitable for meeting an individual child’s presenting needs.

Element 3 – Reviewing and monitoring

At the same time as we are putting these trauma-informed actions into place, we need to have ongoing assessment strategies in place to ensure that we remain informed following the initial assessment. Therefore, whether it works from the same tool as the initial assessment or not, there has to be some metric by which progress towards intended recovery outcomes can be measured to assess if the children are benefiting from the therapeutic care that they are receiving.

If a provider can acquire compelling evidence to suggest that the children in their provision are being supported to overcome developmental trauma and meet their recovery goals, then they will not only have a clear idea of how effective they are being, but they will also have record of exactly the sort of justification that bodies like Ofsted are looking for to indicate integrated therapeutic care.

Additionally, this monitoring information can also indicate where it is necessary to adjust the individual response that preceded it. This can be for positive reasons as well as a negative indication that care isn’t working. It might be that a child has successfully met a development goal and the short-term intervention that contributed to it is no longer necessary, or the child themself may have proactively raised a suggestion of their own in a key working session that they would like to be supported to attempt together.

Elements 2 and 3 shouldn’t be confused for temporary phases of a child’s care that occur one after the other and can then be forgotten about. Both occur in a constant cycle throughout the entirety of that child’s time in placement and require continual, active involvement to monitor and review the impact of care and, if necessary, reformulate the application of that care accordingly.

The reviewing and monitoring element of the TIER system involves an individual TIER tracker that is examined in monthly therapeutic management meetings between the child’s clinical NMT assessor and the residential manager of the home to ascertain their development towards unmet milestones, their progress in psychotherapy (if applicable) and what care outcomes should be prioritised for the coming month.

Element 4 – Team regulation

Much like elements 2 and 3 are continual factors that repeat throughout the remainder of a child’s care after their initial assessment, element 4 is not a final conclusion of the process but one that has to be considered and carefully maintained at every stage of providing therapeutic care.

In order to actually put the approach devised above into practice, it is a fundamental necessity for the carers providing this care to also receive necessary support. It is a foundational conceit of trauma-informed therapeutic caregiving that grounding, recuperative care and support can only be provided by carers who possess that grounding themselves. If the team of people surrounding a vulnerable child or young person do not feel emotionally safe and stable, then they won’t be able to impart the feelings of safety and stability that are needed for recovery.

There are various ways to ensure that the needs of the care team are met as a continual prerequisite to meeting the care needs of the children placed in the home, many of which can be identified if not addressed in management supervision and oversight. The TIER system addresses this element through the caring for carers model. This involves providing the carers with frequent clinical supervision, in the same vein as is mandated for other caring professions such as counsellors and psychotherapists.

Next steps

If you are a provider of therapeutic care for residential children’s homes, then we sincerely hope that the information set out in this article provides an illuminating and constructive insight into the expectations and possibilities that are available to you in meeting the complex needs of the children and young people within your provision.

This is also a topic that we are eager to elaborate upon further, where it seems there are any further obstacles to achieving these goals, so if you have any questions for us about how best to apply this, or would like to inquire about any of our services or an in-person discussion, please get in touch on 01282 685345 or at office@jsapsychotherapy.com